Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy: Basic Issues to Consider in Traumatic Brain Injury Litigation

Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy (CTE) is a neurodegenerative condition that causes changes in behavior, cognition and mood in individuals with a history of repeated blows to the head. It was first studied in the early 20th Century professional in boxers and referred to as “punch drunk syndrome” or dementia pugilistica. The diagnosis has gained recent attention in the media as the subject of various lawsuits brought by contact sports athletes, such as the NFL concussion litigation. It was also the subject of the feature film “Concussion.”

In October 2018, CTE was the subject of a decision by the Supreme Court of Ohio in Schmitz v. National Collegiate Athletic Association, in which the widow of a former college football player sued Notre Dame University and the NCAA, claiming that the defendants failed to notify, educate and protect the decedent from the effects of repeated head trauma during his college football career. Although the decedent played football (and suffered head trauma) in the 1970s, the suit was brought within two years of his being diagnosed with CTE in 2012. In determining whether the suit was time-barred, the Supreme Court had to address the medical aspects of CTE and determine whether it was a latent condition that would invoke the discovery rule, thereby tolling the statute of limitations on the claim until the decedent knew or should have known that he had been injured. The Court found that the complaint did not conclusively establish that the claims were time-barred, because it did not allege that the decedent experienced symptoms of neurological impairment between the end of his college football career and the time of his CTE diagnosis, or when those symptoms first appeared. Because the determination of those issues would require discovery, the Court found that the trial court had erred in finding that the statute of limitations barred the claims.

Cases like Schmitz are likely to become more prevalent as public awareness of the effects of repeated head trauma increases. However, attorneys defending cases involving claims of mild traumatic brain injury or concussions arising out of single incidents should have a basic understanding of the medical aspects of CTE in order to adequately defend against allegations that a person is likely to develop CTE following a single, isolated instance of head trauma.

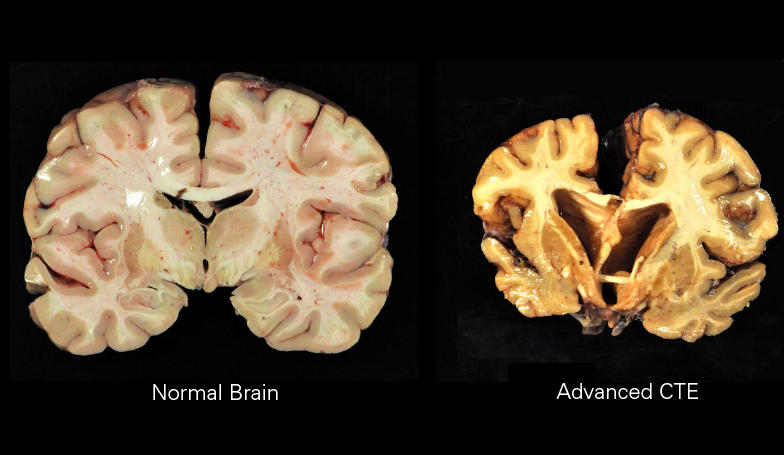

CTE involves a number of specific pathological findings that distinguish it from other neurodegenerative diseases and dementias. Main pathological components of the condition include reduced brain weight caused by atrophy in certain regions, deposition of tau protein TAR DNA-binding protein 43, and white matter changes. Beta amyloid plaques are less prevalent in CTE than in Alzheimer’s dementia. The early presentation in Alzheimer’s dementia is memory decline, whereas CTE’s early presentation involves more behavioral anomalies.

Since CTE was identified identified in deceased former NFL players the early 2000s, research on the condition has yet to answer certain questions. First, it is unknown why only a small subset of professional athletes with a history of head trauma or subconcussive impacts develop CTE; the vast majority of individuals who play football or other contact sports professionally do not eventually develop CTE. Second, the amount of trauma needed to cause CTE to develop, and over what period, is unknown. For example, former New England Patriots tight end Aaron Hernandez was determined to have one of the most advanced cases of CTE ever identified at the age of 27, but many athletes with much longer careers have not developed CTE.

CTE is a specific medical condition that can be definitively diagnosed only upon a post-mortem microscopic examination of brain tissue by a pathologist. See, e.g., Turner v. NFL (In re NFL Players’ Concussion Injury Litig.), 307 F.R.D. 351, 397 (E.D. Penn. 2015). There are currently no tests that can definitively diagnose CTE in living patients. Accordingly, any suggestion by an expert witness that a living person has a CTE diagnosis is not based on any valid scientific methodology currently available. And, because the memory and behavioral symptoms associated with CTE are not specific to CTE and may be due to a variety of other medical or psychological conditions, CTE cannot be diagnosed based on memory or behavioral observations alone. See Turner v. NFL, 307 F.R.D. at 39 (discussing lack of medical consensus regarding the clinical symptoms of CTE). As explained in Turner, the link between the injuries sustained by professional athletes and the development of neurodegenerative conditions like CTE is the subject of considerable ongoing controversy.

Accordingly, attorneys defending concussion claims should be on the lookout for litigation strategies that attempt to link concussions to CTE, and be prepared to address whether such analogies are appropriately admitted into evidence at trial under Daubert v. Merrell Dow Pharmaceuticals based on the current state of the medical literature on CTE and the specifics of a plaintiff’s case.